I used to look upon hyper-specialists and PHDs with envy.

How the hell, with all the realms of knowledge to explore, can they possibly spend 90% of their studies on just one field of inquiry? They must be masters of self-control!

You see, I love literature. It’s my favorite subject.

But if it’s all I read for even just a few weeks, I start to crave history, philosophy, or a natural science — not to mention other books on economics and psychology, or the occasional work of spirituality.

And literature isn’t small. It’s a huge field.

Some people devote 80+% of 7 years of studying to only the English novel, or the English poem in the romantic period, or to just one poet!

I was, and still am, impressed that a person can devote such a large portion of their time to primarily learning about one topic, be it colonial period of American History, biophysics, or anteaters:

My admiration, however, is no longer tainted with envy.

I’ve learned that my appetite for wide reading is an unalterable fixture of my personality, thus, I can, I have to, accept it.

And acceptance and envy are never roommates in the soul. When one moves in, the other packs its bags.

I am not one of these hyper-specialists, nor will I ever be.

I have a temperament which makes the selection of one field or topic impossible. And I suspect many of this blog’s readers (thank you!) do as well.

The good news is that this temperament — this knowledge lust — is beneficial, not just in a self-gratifying way, like an Fboy choosing to sleep with many women rather than committing to one, but in a practical way as well.

It’s not just the achievements of the polymaths like Da Vinci, David Foster Wallace, or Benjamin Franklin I have to support this notion.

Books have been written about the success of generalists.

For example, in the book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, David Epstein notes that proficiency in, and even just exposure to, a wide range of subjects and skills often accompanies success in a variety of disciplines, from sports and writing to business and the sciences.

One reason he gives is that wide exploration allows for a sampling period.

He found that many successful people have a sampling period where they try out different things and, while picking up transferable skills and knowledge from each, also come to understand themselves and which field is best suited to their particular set of interests and talents, thus allowing them to pursue the field in which they’re best constituted to succeed.

This is the idea that inspired me to write about how to use wide reading to find your calling.

Another reason Epstein gives is that generalists, having developed mental maps of many different topics, know where to look to find solutions.

A biologist, with at least basic knowledge of the fundamentals of chemistry, physics, and the other sciences, can productively search those other fields for methods and information that will help them answer their biological question.

I recommend reading the book if you want more reasons to follow your wide ranging interests.

That said, I’m not discounting specialization. You can specialize while building breadth as well.

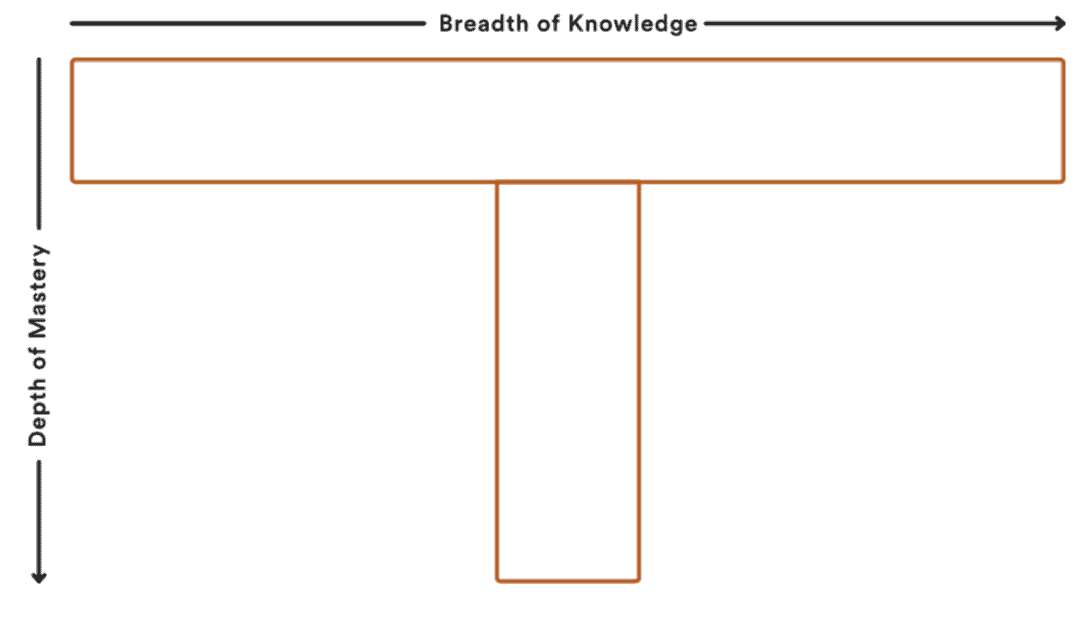

Take a look at Hemingway’s T-shaped learning model:

He thought the ideal self-education was one that supported mastery in one skill and proficiency in a lot of others.

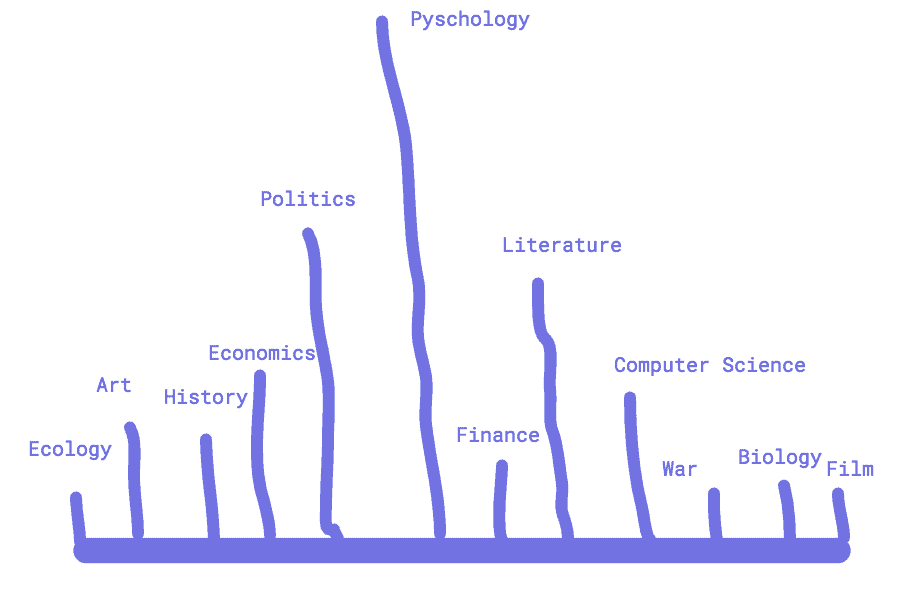

I love this idea, though I prefer a graph with a bit more nuance.

I believe the best way to approach lifelong self-education is to nail down a subject you want to spend a lifetime mastering, as well as around 3-5 you want to be well-read in, and a whole bunch you want to have an outline of should you want to dive deeper for a specific project or problem.

Here’s an illustration of what I mean:

In this case, the person is mastering psychology — or, more reasonably, some branch within the field.

They’re well-read in literature and politics (and sort of economics), while having intermediate knowledge of art, history, ecology, finance, computer science, war, biology, and film.

Those lines are meant to be straight by the way. Fortunately I’m not pursuing drawing or neurosurgery.

Any particular person’s graph will obviously change as their interests and needs do, but it’s a fun thought experiment to select those top 3-4.

You could do the same for skills as well, though skills often come hand in hand with subjects — e.g., a scholar of literature is a master at creatively reading and writing about literature, or, in some cases, producing literature of their own.

Anyway, this is how I rationalize to myself the value of my knowledge lust, my intellectual infidelity…

If you think you might be a polymath, check out the 5 personality traits of successful polymaths.