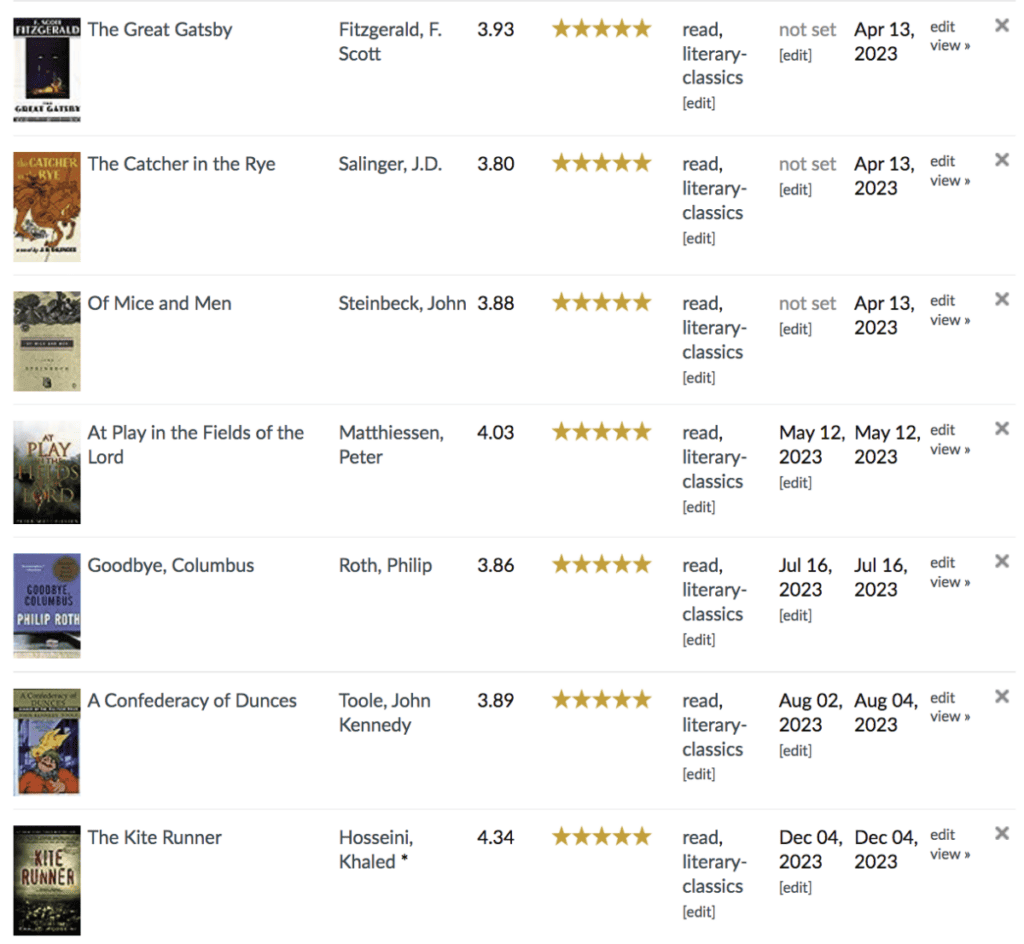

Over the last three years I’ve read a lot of classic novels.

Here are some of my favorites from last year:

The problem is, I read most of them far too quickly…

Only recently did I discover how to read a classic the optimal way — that is, carefully and slowly, in the way they deserve to be read.

I learned to consume them in a contemplative way that not only enhances your ability to understand, talk about, and retain the classic novel, but also enriches your intellectual faculties of imagination, analysis, vocabulary, and reflection, while allowing you to gain serious wisdom and enjoyment from the experience.

There’s a name for this immersive style of reading. It’s called deep reading.

Outside of academia, it’s a bit of an anachronism, a rebel in modern-day society’s mission for efficiency and speed at all costs.

But there are some readers who still do it, and profit greatly from the practice.

They’re the ones you hear talking eloquently about a novel, making an interesting point about its meaning, or drawing an original connection between it and another work of art or thought.

Today I’ll walk you through my system so you can start to get more out of the classic novels you read:

- More comprehension and retention.

- More spiritual and intellectual cultivation.

- More enlightenment and wisdom.

- More enjoyable and transformative reading experiences.

As the great literary critic Harold Bloom once said, “reading well is one of the great pleasures solitude can afford you.”

Quick Note: Please know that most of these reading strategies are optional. Do them if you find them helpful. If not, skip them. I’m simply sharing what’s worked for me. I’m also sure you’ll find reading techniques that work for you that I’ve failed to mention or discover yet.

Important Reminder: Remember, deep reading is supposed to be a pleasurable experience! So don’t beat yourself up for skipping over steps. Deep reading is also a practice, one that you’ll improve over time. The more you try to do it the better you’ll get. I still struggle to do it here and there myself.

Without further ado, here’s my 3-part system for deep reading classic novels.

Before Reading a Classic Novel

Before reading you’re going to do some work to prime yourself to get as much wisdom and joy out of the classic as you possibly can.

The steps for this are to find the right novel, get some context, pick some aspect of the novel to focus on, and tell yourself you’re about to be impressed.

I’ll now go through each step individually.

1. Pick a Classic Novel That Intrigues You

There’s bound to be some classic novel you’ve been itching to read for a long time now, one that you’ve seen mentioned countless times.

The more the novel’s premise and character arc speaks to you the likelier you’ll enjoy the deep reading experience, and the better you’ll do it. So pick one you want to read, not one you feel you should.

If you’re a beginner, here are some of the classic novels I find highly accessible:

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (I read this every Christmas)

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- 1984 by George Orwell (this was my gateway drug to classic literature)

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- The Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien

Also, I recommend beginners check out my self-study literature reading plan. This includes 14 books that’ll help you get started (includes works of criticism and anthologies and books about the act of reading). Grab it below:

2. Gain Context: The Author, The Culture, The History

As someone interested in the lives of writers and the subject of history, I like to learn a bit about the environment that influenced the creation of the novel.

It’s not only interesting information in itself, but it also enhances the reading experience. It gives me more to think about while I read.

For example, The Lord of the Rings takes on a whole other level of intensity when you know that Tolkien was a linguist and that he imagined middle earth during his time in WW1 as a way to escape from the horrors around him.

With this knowledge, the epic story of good vs evil becomes a mirror of our own troubled past.

Gaining some context also supplies you with material that makes it easier for you to draw connections, which in turn helps you retain more of what you read, while also generally enhancing the experience. It just feels good to make connections.

For instance, I’m currently reading Don Quixote, and at the same time I’m reading a history about Imperial Spain, the time period in which the novel was written.

Some of the jokes hit me a lot harder when I know the historical context. La Mancha at the time was a boring place with very little noble about it, so him hailing from there is more ridiculous.

And if I didn’t know he was living in a time right after the glory days of knighthood and in effect trying to restore those times, the whole story wouldn’t be nearly as comical and relatable (for we all miss something from the past).

Anyway, I don’t like to get too bogged down with this. I usually spend under an hour doing it. I might use Wikipedia, but my favorite method is using an introductory lecture by a YouTuber like Benjamin Mcevoy, who creates awesome intros.

You can sometimes also find introductory lectures from college professors, which are great as well.

Some people like to read the introduction in the front of the novel, and I do sometimes, but sometimes I don’t want the plot spoiled so I avoid them (though the plot is really only 1 minor reason to read a classic).

3. Pick Something to Pay Special Attention to

Aside from enjoying the novel’s story and insights into human nature, I like to also learn something specific from a reading of a classic.

That could be something about how fiction works, the prose style, a specific character’s arc, history, or some big theme or philosophical question the novelist is addressing in their story.

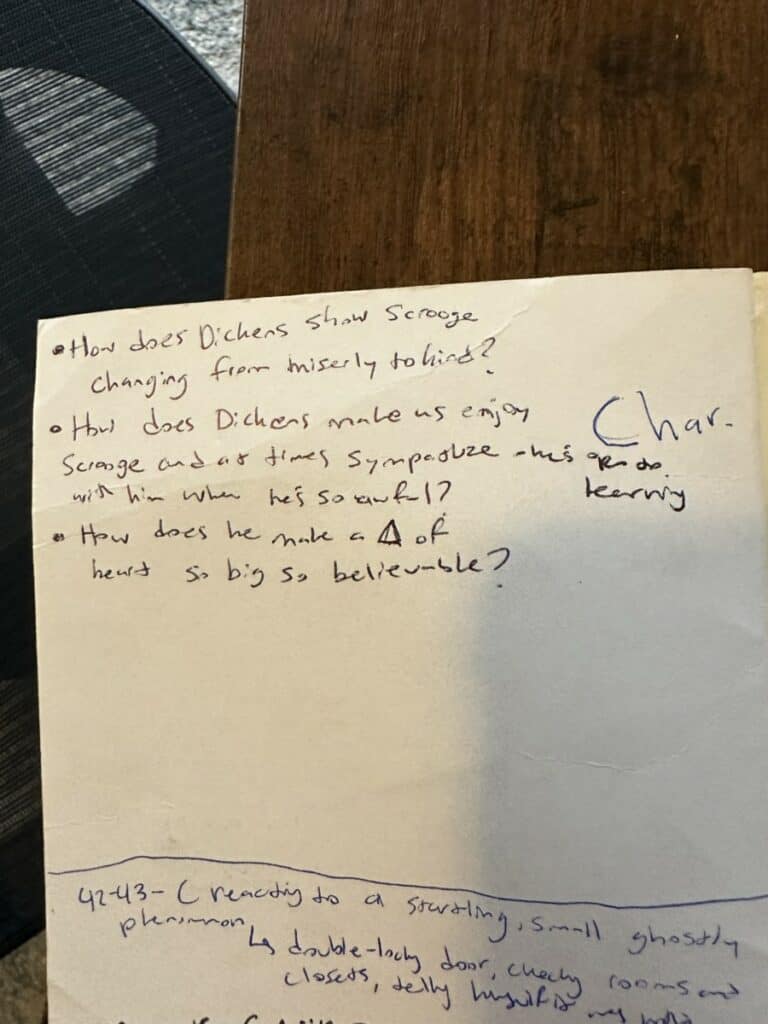

For example, before reading A Christmas Carol, I was curious about how Dickens made such an extreme change of heart believable, and such an atrocious man somewhat likable, even pre-transformation.

This was a craft-based focus.

I could’ve read it focusing on the moral-philosophical question, “why is greed bad?” and I would’ve had a totally different reading experience!

Can’t think of a question or area of focus? Sometimes the introductions you read or watch will give you ideas.

For instance, the professor in the intro to Don Quixote lecture told me that the story still has serious relevance today. I asked myself “why?” and have been trying to figure that out as I read.

Someone else reading Don Quixote might want to learn about 17th century Spanish culture or the principles of satire. It depends on your goal and what you want to learn.

Sometimes I’ll write the question relating to my focus on the inside cover of the book. This serves as a reminder. I’ll reread it sometimes before I go read.

For instance, here’s what I wrote on the inside flap of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol:

I’ll notice other things while I read, of course, but this will be my main focus, and underneath the questions on the inside flap I’ll write down page numbers corresponding to passages that relate to whatever I’m focusing on investigating. (you can see I did this above)

4. Believe There’s Magic & Wisdom Inside

Whenever I’m feeling a bit grumpy about going to a social event with people I hardly know, I remind myself that every person has the ability to surprise me and, as Thoreau famously said, is my teacher in some way.

This simple reminder makes me more outgoing, and at these dinner parties and work events I regularly find that the people I speak to end up surprising me with their stories, wisdom, or senses of humor.

Take this same approach to reading classic literature.

Psych yourself up a bit before a reading session. Remind yourself that this book has the power to transform a life with its wisdom and magical storytelling.

If the classic book wasn’t capable of this, it wouldn’t still be on recommended reading lists and the tongues of intellectuals across the globe.

When you go into a book with the intention of being surprised, you’ll read it more closely and with more focus, and as a result you’ll have a more emotional and enlightening reading experience.

While Reading a Classic Novel

These steps are moreso tips; they’re less sequential. I do each one at various points throughout the reading of a classic novel.

They include tracking new characters, writing chapter summaries, writing in the margins, reflecting on what I’ve read, and capturing my favorite passages into my literary commonplace book.

5. Keep a Character List

In a notebook or on one of the blank first pages of the novel, keep a list of characters in the story.

I like to do this on a separate piece of paper since sometimes the party of characters grows too large for an inside flap to handle.

How character lists work is simple. Whenever a new character comes into the story, write a little blurb about who they are.

This will be a great reference for you, especially when reading something by a writer like Tolstoy, who creates lots of characters.

This practice will also force you to slow down and really meet the character. You’ll shake their hands, have a chat, and get a sense for who they are.

You’ll also naturally start to think about how they’ll affect the story and the lives of the other characters you already know, which will make you more invested and more knowledgeable about the plot dynamics of the classic.

You can add new characters to the list at the end of a reading session so as not to interrupt the flow of the read, or you can do it immediately when they arrive on the scene.

Try out both and see which works for you.

6. Write Chapter Summaries

In The Well Educated Mind, Susan Wise Bauer recommends writing chapter summaries at the end of every chapter, and then re-reading them all after you’ve finished the book.

I spent a long time ignoring her advice, but now I’ve started doing it and it’s so worth the thirty seconds it takes.

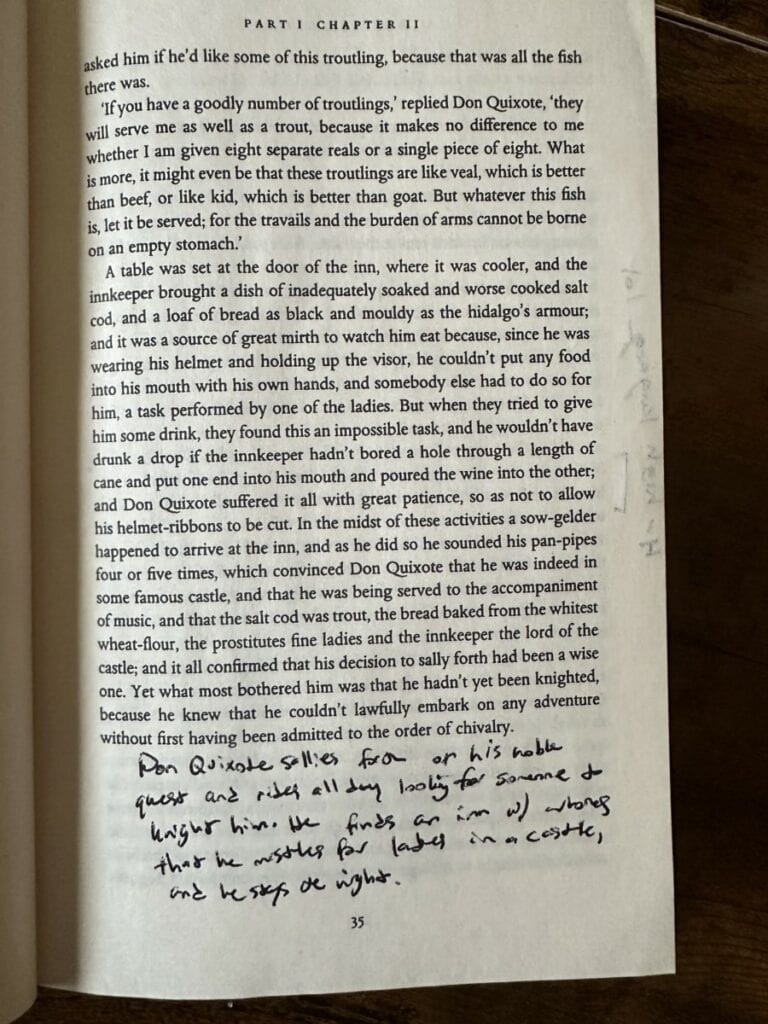

Here’s one I wrote for chapter 2 of Don Quixote:

As you can see, it’s nothing special, just a review of the key events:

Chapter summaries are a pretty easy thing to do. Simply jot down 1-2 sentences describing the main events of the chapter you just read.

Doing so will help you remember the major events of the novel, allowing you to reference them in conversation and writing.

How does it help you remember? By trying to remember what you just read you’ll be doing active recall, a science-based memorization tactic. Plus, you can review these summaries later on.

But writing chapter summaries does something else useful too. By knowing the events of the story, you’re able to come up with an interpretation of that sequence of events.

In other words, you’ll be able to answer the question, “what was the story about?” using not only language about what happened to the characters but also language about the message the author is trying to convey.

A Little Lesson on Interpreting Fiction

Your interpretation will differ from other peoples’ interpretations, and that’s okay! That’s what’s supposed to happen. As long as you can defend it with evidence, you’re doing a great job.

For instance, I told my friend I thought the Confederacy of Dunces was about a shy intellectual outcast who uses big words and esoteric knowledge to convince himself that he’s better than the people who spurn and dislike him, and that it his insecurity and behavior that stems from it, not his nerdy personality, that causes his loneliness.

My friend read the story a bit differently, distributing his attention in a unique way (as we all do), and therefore he came up with a different interpretation.

He thought it was at its core a story about the folly of intellectualism (which is probably more of what the scholars would agree with).

But getting it right isn’t the point!

You take the meaning that helps you achieve what you need or handle what you’re going through in life.

I myself had been reading the novel at a time when I had shut myself off from the social world a bit, so I was primed to project my own feelings of loneliness onto the protagonist.

7. Do Marginalia & Underline Passages

Marginalia is the act of writing in the margins of the book.

It promotes active reading and allows you to read more deeply by putting you into a conversation with the author.

Most of my marginalia for classic novels falls into these five categories:

- Drawing Connections: I have so many names of people in my life in the margins because a character reminds me of them. I also draw connections to other works I’ve read. Sometimes I’ll note intertextuality, or relate an idea to one of another thinker.

- My Special Focus: Use a highlighter to highlight passages relating to the special thing you’re paying attention to.

- Questions: A question mark is a sign of me wondering what’s going to happen, or maybe it’s a sign that I’m a bit confused about what’s going on.

- Writerly Choices/Techniques: When I notice an interesting choice the writer has made or craft technique they’ve used, I like to write a quick blurb about it.

- Summaries: If I really like a piece of writing, sometimes I’ll just summarize what the author said in the margin and draw a vertical line across the sentences to mark the part of the page I’m referring to.

Also, a lot of the time I’ll just write “Yes!” or “So true!” as a note to my future self to read these passages again.

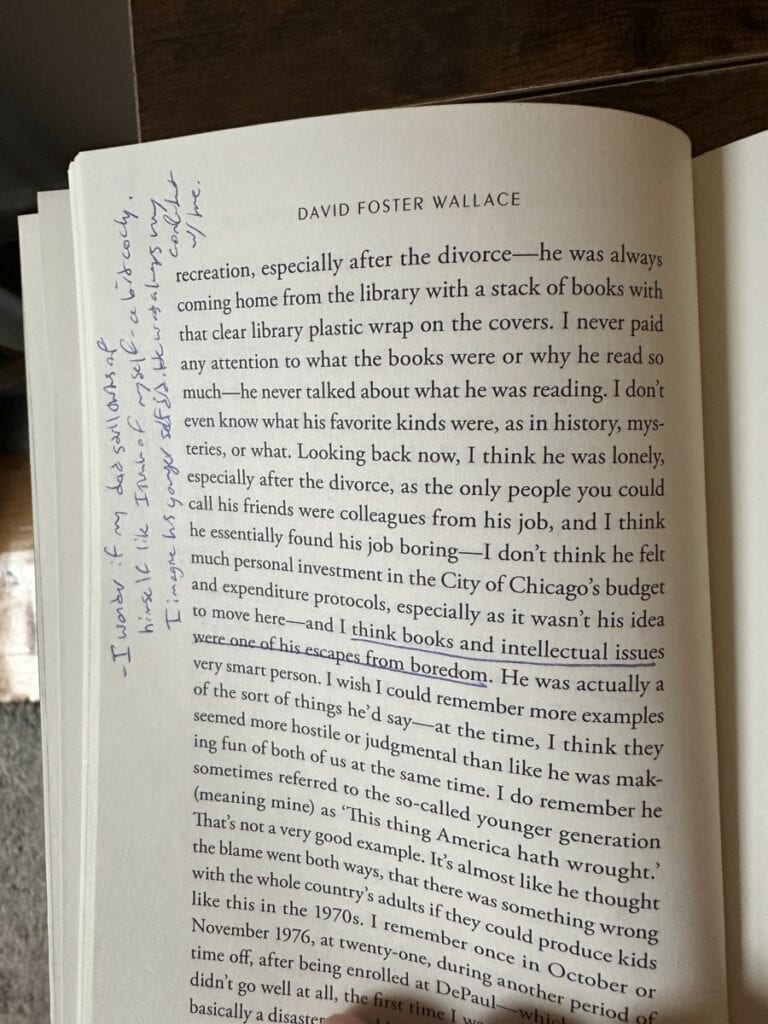

Here’s some of my chicken scratch marginalia:

You might choose to return to your marginalia after reading, especially if you’re going to write a book review, but that’s not the only reason for doing it.

Writing is thinking. By writing in the margins you’re stopping and thinking about what the author is saying. You’re engaging with the text on a deeper level.

You’re having a conversation with them or with the characters. You’re taking a moment to reflect on yourself and your world, which is where the self-transformation and intellectual growth occurs.

8. Take Five Minutes to Reflect After Each Reading Session

After you finish a reading session, spend a few minutes thinking about what you’ve just read.

Was there a sentence that resonated with you? A moment in the story that had you in tears or laughing out loud? An idea or description that blew you away?

Whatever marked the high point of the reading session, reflect on it, and ask yourself why it rang so true to you.

By doing this, you learn about yourself, and you also end up remembering more of what you read, which allows you to bring it up later in conversation or in your book review. (step 13).

Here’s an example.

The other day I was reading Philip Roth’s American Pastoral on the train into NYC.

When the train reached my stop at Penn Station, I closed the book and asked myself, “what was the most interesting part of the 10 pages I just read?”

For me, that was the few pages describing the protagonist walking around his new town in the countryside and pretending to be Johnny Appleseed.

Then, after mentally recapping the main points of those pages, I asked myself why I picked that section.

My answer was that I love to walk, and dearly miss walking, which I’ve been neglecting in the cold winter weather.

I’m realizing now as I’m writing this that since that experience, I’ve actually increased my daily step count. The reflection process actually changed me!

Let me emphasize a key point.

You can’t possibly retain and reflect on every deserving part of a classic novel. They’re too rich and dense.

Just pick the ones that ring most true to you. It’ll make the reading experience all the more enriching. Plus, you can always read it again. Classics are meant to be re-read.

Pro Tip: I’ve heard of people re-reading their underlines and marginalia at the start of every reading session, as a type of spaced repetition. I’m always too eager to read, but if you can do this, try it out.

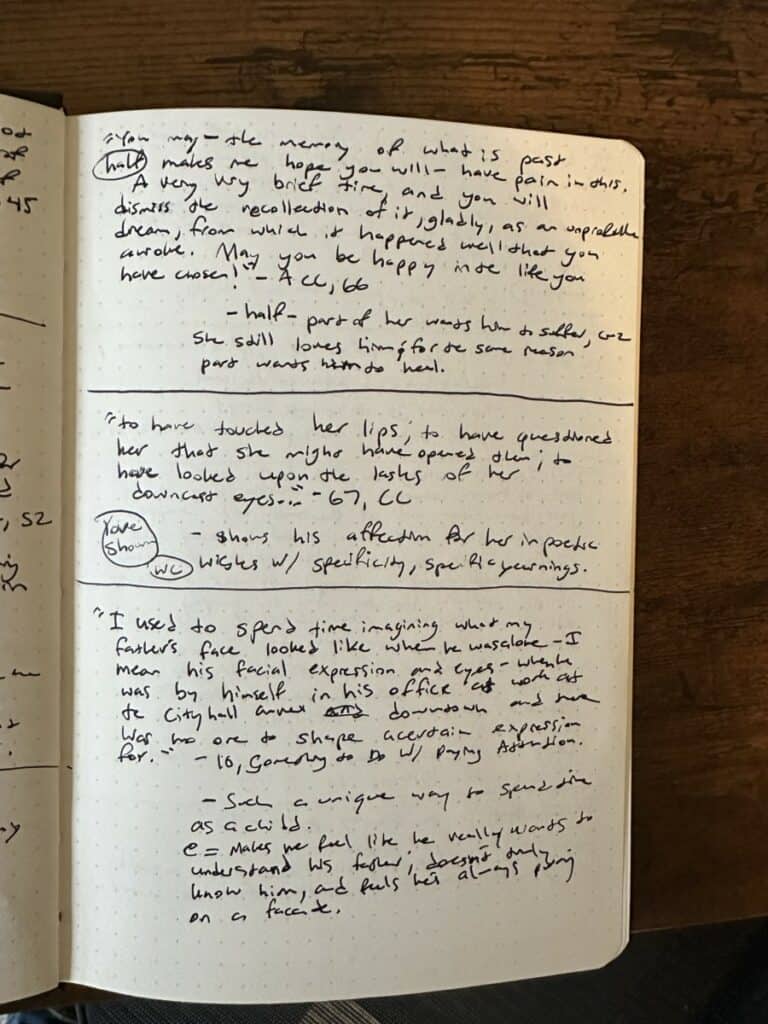

9. Capture Your Favorite Sentences, Passages, & Scenes

Take your reflection a step further and start capturing your favorite sentences, passages, and scenes from the book into a literary commonplace book.

Here are some of mine from A Christmas Carol and DFW’s Something to Do With Paying Attention:

I like the Leuchtturm 1917 dotted journal for this. It’s the perfect medium size and comes in a bunch of different colors.

You can write down these passages immediately when you come across them. Or you can do it in intervals, like once a week, or once every 50 pages. Whatever works for you!

I used to do one big transfer at the end of reading the book, but I found that was a big mistake because it always felt like too much work and I’d end up skipping it.

Better to do it in short bursts over the course of the reading period.

Oh, by the way, some passages will be too long to copy down by hand, so just write the page numbers, a summary of what was written, and your thoughts.

I did this recently for the tragicomic train accident scene in On Something to Do With Paying Attention by David Foster Wallace.

What to Write Under Your Captured Beauty & Wisdom

Under your captured sentence(s) simply write why you decided to keep it. This will tell you something about your taste.

Go a step further and and closely analyze the passage like a scholar might. Or write your thoughts down and enter into conversation with the author.

Whatever you reflect on and think about, this practice will promote a deeper reading experience.

It’ll also allow you to build a repository of beauty, wisdom, and truth to which you can return when you want guidance, connection, or perhaps just pure aesthetic pleasure.

Plus, rumination is a pleasure and can often lead to insight and breakthroughs.

Memorizing Your Favorite Passages

Another cool thing you can do is memorize your favorite sentences or passages of the novel.

That way, if a totalitarian regime ever locks you away in a dark underground cell at least you’ll have a well-stocked mind full of wonderful phrases to entertain yourself.

This is what I’m doing for Don Quixote. Yale also offers a cool online course on the American Novel After 1945. Consider doing the course and reading all the classics she recommends.

Pro Tip for While Reading a Classic: If you can, find a course on the classic novel. Reading along with a professor or expert in the classic will help you notice things you might’ve otherwise missed.

After Reading a Classic Novel

Congrats! You finished the classic novel.

Now it’s time to really get to know the book and your opinion of it — in other words, what the novel was about and what you liked/disliked about it, and why.

I skipped this part of the process for the longest time, and it really held me back intellectually.

It was when I started doing this that I actually started to remember the books I read, make them a part of my mind, actions, and soul, and have something interesting to say about them.

So don’t skip it (especially step 13).

This phase doesn’t have to be hard or take that long.

Think of it like having a 1:1 dinner with someone you met at a party and really hit it off with. Now’s your chance to really get to know them and connect.

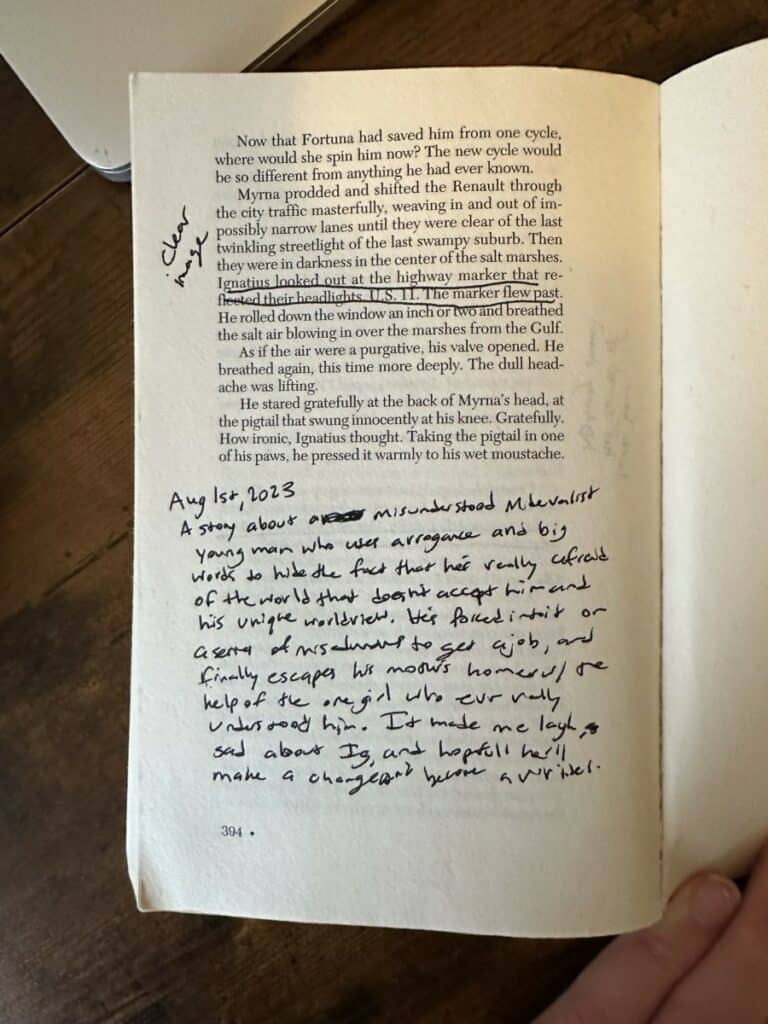

10. Write a Quick 3-Sentence Summary in Back of Book

When the great essayist Michel de Montaigne would finish a book, he would immediately write a short paragraph on the back flap saying what the book was about and what it meant to him. Then he would date it.

Take a note from the great and do the same. Here’s one of mine for Confederacy of Dunces (SPOILER):

It’s nice to do it right when you finish.

That way you’ll get an immediate impression of the book down on paper, and you can look back on it ten years later during your second read and say, “holy shit that’s what I thought it was about? What a dummy. What a philistine! Look how much I’ve grown intellectually. Look how much I see now that I couldn’t see before!”

It’ll also get your gears cranking and plant the seed for what will become a full book review (step 13), which is where you really start to understand what the book is about and what your opinion is of it.

That’s when you become one of those people who are able to effortlessly engage in book talk, people who still make me feel a bit out of my depths.

If you do step 11, it’ll also ensure that you have your own idea about what the book means before you start reading other peoples’ opinions.

This way you’ll maintain your originality and protect yourself from just believing other peoples’ interpretations.

11. Re-Read Your Underlines & Marginalia

Go through the book and read the notes you took in the margins and the passages you underlined.

As you do this, keep it in the back of your mind that you’re going to write a book review of this novel, and that some of these underlines and thoughts might be particularly useful for doing so.

Now is also a great time to also do something called “journaling off the page”, where you pick one passage that really resonates with you and respond to it in longer-form on a separate sheet of paper.

For example, the passage you like might be about unrequited love; you could go write down your experience with it, or try to describe the impact on the spurned lover.

This exercise forces you to get closer with the author and the text, and helps you learn a lot about yourself in the process.

12. Read Secondary Literature (Optional)

Sometimes I like to read secondary literature about the novel to gain a broader and deeper understanding of it.

You can often find literary analyses and summaries of the novel from a YouTuber, SparkNotes, or SuperSummary.

You might also be able to find online lectures or discussions on the novel, either in podcast or video form.

I really like Tristian and the Classics’ videos.

For example, here’s his in-depth review of Great Expectations:

Watching these will not only teach you more about the book. It’ll also teach you by example how to think about novels, what to notice and expound upon.

In other words, by watching a great reader talk about a book, it’ll make you a better reader and book reviewer yourself.

13. Write Your Own Book Review

I’m on a mission to review every book I read. Here are 10 reasons you should too.

I started doing this because I looked back on all the books I’d read last year and was appalled by how little I remembered about them.

I wanted to turn myself into the type of person who retains the lessons of the books they read and can eloquently express their opinion of the book even years after reading it.

Writing reviews helps me do that.

Benjamin Mcevoy, a former Oxford lit student who now teaches literature online, made a very good point in one of his videos that you don’t really know what you think of a book until you sit down and write about it.

Why? Because writing is organized thinking. Writing forces you to turn muddy impressions and feelings into clear, crisp sentences. Otherwise the writing will be intolerably confusing and bad.

If you like to be in front of the camera, you could also film yourself speaking about the book, using what you’ve written as a script.

How to Structure Your Review

As for the structure of the review, don’t stress too much over it. This isn’t a school book report. It’s for you to learn about the book and to clarify your opinion of it.

I like to follow this structure:

- 1 paragraph summarizing the book’s story.

- 1 paragraph on the core message of the book.

- 3 parts I loved and why (could be character, a scene, a sentence, etc.,).

- 3 things I learned about writing.

See my review on DFW’s Something to Do With Paying Attention for an example. This one recently helped me land a freelance writing gig reviewing new indie novels. (another reason to write reviews, make some grocery money!)

I’ve played around with other structures as well — see 3 reasons autodidacts should read Martin Eden.

Basically, use a structure that helps you get what you want out of the book.

If you want to learn lessons about human nature, write 5 of the author’s insights into human nature. Want to explore the theme of love? Write about the author’s take on love.

If you did step 3 and paid attention to one specific philosophical question or aspect of the novel, definitely write a bit about that in the review. Make it your own and have fun with it.

14. Apply the Lessons You Learned

All classic novels contain lessons.

Sometimes the main lesson will be obvious to a wide range of readers.

Other times you’ll have a takeaway that no one else has had, because you’ll be reading it as someone with a unique set of experiences, problems, and opinions.

I’d recommend coming away with at least one lesson from each book you read, and then working to really apply it.

“How many a man has dated a new era in his life from reading a book.”

— “Walden”

Instead of talking about this, I’ll give an example of what I mean:

A Lesson on Keeping With the Times via Don Quixote

I’ve been reading Don Quixote over the past few weeks, and it’s been making me think a lot about the dangers of living in the past.

The hapless hero in the story wants to revive the aristocratic culture of the Spanish 15th century so badly that he actually starts to pretend to be one of the knights that dominated the battlefields in those glory days he holds so dear.

As a result, he lives like a fool, misinterpreting everything because his algorithm for comprehending reality has been corrupted by desire.

It reminds me of the old man who refuses to learn to use new software at work, under the illusion that he doesn’t have to and that things will continue to be done as they always have been.

He sees what he wants to see, that times aren’t changing. But they are!

At the relatively young age of 27, I’ve already noticed myself making this type of mistake.

I’ve long neglected marketing this blog, for example, I think out of the silly view that Jack London or George Orwell and the other authors from the past I admire would just focus on writing, and therefore that’s what I should do.

But that bad idea did nothing but hurt the growth of the blog.

And, thanks in part to Cervantes, I’ve come to see that, and am now accepting that I have to market this thing if I want it to grow into a real business that can help inspire more people to read and follow their intellectual curiosity.

Speaking of which, consider joining my email list to receive a free 14-book reading plan for self-learning English Lit (what I wish I’d had when I was starting out):

In the weekly newsletter you’ll receive helpful tips and articles about self-education, reading the classics, and polymathy.

Alright, your deep reading journey is complete… for now 🙂

Come Back Again in a Few Years

My reading of Martin Eden at 24 was vastly different from my reading of it at 27.

In just 3 years my life had changed dramatically. My job was different. My relationships had changed. My social circle was new. I was on the West Coast instead of the East.

Since I was different, so was my act of reading. I noticed new things. My distribution of attention was different. I interpreted scenes and sentences in new ways, ways that related to my current life.

This is the great thing about classics. They reward re-reads.

They’re not like a fast-paced thriller novel where you read it once and doing it again would feel like a waste of time.

In classics, the plot matters, but it’s not the main reason for reading.

Classic novels are filled with ideas, insights, and beauty, and they’re endlessly deep — you can interpret them in so many different ways, read them profitably through so many different lenses (this is what many lit scholars spend their time doing).

They transport you to different worlds, into different minds, and offer up opportunities to reflect on your own life.

So return to your favorite classics.

Revisit the characters you loved and the passages that captured your heart and mind. See it through the eyes of the new person you’ve become. It’ll be a novel experience — I guarantee it.

Hey, if you want to self-learn literature systematically, check out my English Lit self-education roadmap for beginners. Inside you’ll find 12 steps to gain a firm foundation in this magical subject as well as some great courses, books, videos, and resources, all arranged in a logical order.