Whenever I’m in need of some motivation to hit the books, it helps to review what America’s founding fathers were able to accomplish through self-directed study.

Each of these men, in their own unique way, used self-education to improve their character and acquire useful knowledge and skills that enabled them to productively contribute to the founding of a new nation.

Whether it was Benjamin Franklin teaching himself to write persuasive prose, or Madison pouring over ancient history and analyzing Roman governments to inform the constitution, I always find these stories inspiring.

My hope is that this review of their self-directed educations will also encourage you to pick up a book or chart your own course of independent study that will help you make a positive change in the world you’d like to see.

Along the way you’ll also pick up some useful techniques that’ll help you self-learn more effectively.

Benjamin Franklin: The Autodidactic Polymath

Benjamin Franklin was a renaissance man by every definition of the word. He taught himself science, business, writing, government, diplomacy, and many other valuable skills.

How did he do it?

He made learning a priority, setting aside an hour every morning to “prosecute the present study”.

At one time that was electricity, at another time, the French language.

But the most interesting to me has always been his systematic approach to teaching himself how to write.

Using Copywork to Teach Himself to Write

The learning process he concocted for himself was based on studying and imitating great writing.

“About this time I met with an odd volume of the Spectator. It was the third. I had never before seen any of them. I bought it, read it over and over, and was much delighted with it. I thought the writing excellent, and wished, if possible, to imitate it.” — Ben Franklin, Autobiography of Ben Franklin

To learn from an article, he would first read it closely and jot down a short hint of the main sentiment each sentence was effectively getting across.

A few days later, he’d come back and try to replicate the article, using the sentiments as a guide, and essentially turning the hints into full sentences.

Next, he’d compare his version to the original, and mark where and why the original was better than his imitation.

At first he struggled with this exercise and discovered that he had a lot to learn about effective prose.

But, after a lot of deliberate practice, he found that his versions were in some ways better than the originals.

By comparing my work afterwards with the original, I discovered many faults and amended them; but I sometimes had the pleasure of fancying that, in certain particulars of small import, I had been lucky enough to improve the method or the language.”

He used variations of this exercise to improve other aspects of his writing.

For example, to improve his active vocabulary, he tried to turn the articles into poems:

“But I found I wanted a stock of words, or a readiness in recollecting and using them. Therefore I took some of the tales and turned them into verse; and, after a time, when I had pretty well forgotten the prose, turned them back again.”

And he would even sometimes shuffle up the hints and then try to reorganize them in order to learn the art of composition:

“I also sometimes jumbled my collections of hints into confusion, and after some weeks endeavored to reduce them into the best order, before I began to form the full sentences and complete the paper. This was to teach me method in the arrangement of thoughts.”

Writing was an incredibly important skill for revolutionaries and statesmen before, during, and after the American revolution.

Like today, those who could write could establish themselves as experts, persuade others to their side of thinking, and inspire the change they wanted to see in the world.

Without the skill of writing, it’s hard to believe that Franklin would have reached anywhere near the political and social influence he had.

Are you destined to be a polymath? Check out the five personality traits of effective polymaths.

Try it Out Yourself

If you want to learn to write, consider borrowing his self-learning technique.

Go find your favorite essay or article, write down a hint of what each sentence is saying, and try to replicate it from memory. I’ve done this with Rousseau’s essays.

It will be difficult, and you will make many errors, but as my high school Spanish teacher always told me, stress is a sign that you’re learning. Over time your writing will improve.

George Washington: Emulating Great Leaders

Like Franklin, George Washington also used imitative-style learning, but in a different way.

Throughout his career, he studied and emulated the behavior of the great leaders he read about in the classics of Ancient Rome and Greece.

“In his youth, he had been interested in Caesar and had read a bit about him. Later, as an adult, he sought to model his public persona upon Cato—upright, honest, patriotic, self-sacrificing, and a bit remote. Then, fighting for American independence, Washington had a new Roman role thrust upon him, that of the celebrated general Fabius, who defeated an invader from overseas mainly by avoiding battle and wearing out his foe. Finally, after the war, he would play his greatest role, the commander who relinquished power and returned to his farm, an American Cincinnatus.” — First Principles, Thomas E. Ricks

We are often told that we become like the people we surround ourselves with.

Washington highlights that you can sort of hack this social phenomena by reading about great people and devoting energy and attention to copying their behaviors, routines, and virtues.

The people don’t have to be physically around you to rub off on you. They can exist in your imagination and have nearly the same effect.

Learning to Lead & Win on the Battlefield

George Washington was not regarded as an intellectual heavyweight. He was not a fast and eloquent speaker like the rest of the founders. But that’s not to say he was uneducated.

Far from it. His reading of the classics and his reflection after battles, taught him critical thinking, and though he wasn’t known to ramble off facts, he could win on the battlefield, an incredibly practical intelligence he had cultivated.

“to study a situation, evaluate its facts, decide which ones were meaningful, develop a course of action in response to work toward a desired outcome, and verbalize the orders that needed to be issued. Those are the basic steps in critical thinking,” — First Principles, Thomas E. Ricks

Washington’s education and quiet mastery of public persona, leadership, and warfare are reminders that knowledge isn’t always loud and in your face.

Sometimes, the silent person in the conference room is the one with the best understanding of the situation, and is working out a plan of action that, if they were only given some time to develop it, could work with great success.

Slowness does not mean stupidity. Usually, when someone is slow to react, it’s a sign they’re a deep thinker. And patience with them will yield results.

John Adams: A Lover of Books

As a young man, and throughout his life, John Adams was an avid reader.

He taught himself law, politics, history, literature, rhetoric (he was basically Cicero’s reincarnation), and other subjects that were of interest to him.

Though he attended Harvard for college, the majority of his efforts to learn were made in solitude, hunched over a desk reading his books.

While he did study in other ways, such as observing and imitating the lawyers he most admired, his main study method was reading great books by enlightenment authors, ancient Romans, and ancient Greeks.

This love affair with books began in his first year at Harvard:

“To his surprise he also discovered a love of study and books such as he had never imagined. ‘I read forever,’ he would remember happily, and as years passed, in an age when educated men took particular pride in the breadth of their reading, he became one of the most voracious readers of any.” — David McCullough, John Adams

Such wide and reflective reading was no doubt responsible for his rise politically. By arming one with the ability to perform in various conversation topics, knowledge can make a man easier to connect with, and thus more likable, which is essential in politics.

Take what McCullough writes of him in his biography:

“He was lively, pungent, and naturally amiable — so amiable, as Thomas Jefferson would later write, that it was impossible not to warm to him. He was so widely read, he could talk on almost any subject, sail off in any direction. What he knew he knew well.” — David McCullough John Adams

But, like most ambitious students, he went through periods of painful self-doubt.

He often struggled to focus on his studies, and was frequently angry with himself for being too distracted.

At twenty, he wrote:

“I have no books, no time, no friends. I must therefore be contented to live and die an ignorant obscure fellow.”

At one point, he wrote out a rigorous study plan:

“I am resolved to rise with the sun and to study Scriptures on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday mornings, and to study some Latin author the other three mornings. Noons and nights I intend to read English authors… I will rouse my mind and fix my attention. I will stand collected within myself and think upon what I read and what I see.”

The next morning, he slept in and, a week later in his diary he wrote, “Dreamed the day away.”

At age 21, he was still unsatisfied with his self-control, writing the following resolution:

“‘Let no trifling diversion or amusement or company decoy you from your books,’ he lectured himself in his diary, ‘i.e, let no girl, no gun, no cards, no flutes, no violins, no dress, no tobacco, no laziness decoy you from your books.’” — David McCullough, John Adams

Even Presidents Doubt Themselves & Struggle With Self-Control

When reading about John Adams, I felt consoled. I myself have been constantly unhappy with my inability to stick to reading plans or do my nightly studies.

Whenever I skip a few days or fall behind on my reading, I feel a deep sense of failure. It is nice to know that even the former president of the United States, and one of the best legal and political minds of US history, was once in my same position.

The takeaway for me is that if you’re feeling dissatisfied with yourself, you’re probably on the right track.

Dissatisfaction is a sign of ambition, and, though it may take a while, with daily effort and vigilance, you will increase your reading time and your stock of knowledge.

Also, don’t be so hard on yourself. Even John Adams struggled to hit his self-study goals, and look how much he achieved.

Struggling in self-directed study? Maybe you’re making one of these seven mistakes.

James Madison: The Head Architect of America’s Government

James Madison has been called the “father of the US constitution.”

He crafted the Virginia plan, a radical departure from the current form of government, The Articles of Confederation.

And, perhaps most notably, he wrote many of the most influential Federalist Papers, a series of political essays now studied in pretty much every political science department, that sets out to explain the constitution’s benefits and win its ratification.

Without long self-directed study, and careful preparation of facts and arguments, none of this would have been achievable, and America’s government, as well as the ones that emulate it, could look starkly different today.

Though educated formally in the classical tradition, and then at graduate school (he was the first Princeton graduate student), the most significant time of study in his life occurred outside of school.

Madison’s Deep Study of Ancient History

In an effort to improve America’s early, post-revolutionary government, he took to reading history, carefully studying the governments of the past:

“To prepare for the Constitutional Convention of 1787, James Madison studied the strengths and weaknesses of ancient and contemporary confederations. Surveying the political systems of ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, the Swiss Confederation, and the Netherlands, Madison sought models to improve upon the Articles of Confederation. His research contributed significantly to a stronger Union under the U.S. Constitution.” — Visit the Capitol.

James Madison doesn’t get as much attention as the other founders. He flies a bit more under the radar.

But, Thomas E. Ricks, Author of First Principles, said this in a podcast:

“George Washington wins the war that gives us the country. But James Madison is the man who gives us the design of the country we now live in 250 years later.” — Matt K Lewis Podcast

“He decides during the Articles of Confederation period that this thing isn’t working, and a lot of people agree with him, including George Washington. He starts beating the drum for holding a Constitutional Convention. He spends years doing research for it, really approaching the ancient world as a political scientist, looking at how Greek city states worked, how their confederations work, how the republic worked. What do you want to copy from that? What do you want to avoid? Then he goes off to Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention and gives one of the first big speeches that lays out his thinking and what he’s learned. Then, he and Alexander Hamilton, after the convention, lead the campaign to ratify the thing. And then on top of it, in the 1790s, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson basically invent the first form of American politics.” — Thomas Ricks, Matt K Lewis Podcast

If you want to learn more about Madison, and the classical studies of Washington, Jefferson, and Adams, I highly recommend reading First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country.

It was so good I recently lent it to a friend, an act I’m now regretting because I would’ve liked the book for this article… but hopefully my notes and memory have sufficed.

Thomas Jefferson: The Philosopher Statesman

Thomas Jefferson had a lot to say about education.

He believed that an informed citizenry was essential for the survival of liberal democracy, and he went about making this vision a reality by revolutionizing American education, which up until then had been mostly a religious schooling system.

Jefferson felt the library should be the center of the university, not the church.

It makes sense that someone with such strong beliefs about education would have engaged in much of it himself, amassing at one point a library of some 6,500 books, which he donated to the Library of Congress in 1814.

A Lover of Books

Books were Jefferson’s chosen companions, and he centered his life around them, once even describing his reading habits as “canine.”

More than the other founding fathers, who favored the Romans as their models for establishing a new government, Jefferson preferred the Greek thinkers, reading Pythagoras, Socrates, Epicurus, Homer, and Thucydides, among others.

“Jefferson scarcely passed a day without reading a portion of the classics.” — Thomas Jefferson, Rayner’s Life of Jefferson

But he didn’t only read politics and history. He read plenty of literature, including Shakespeare and other novelists of the day.

He was well aware of fiction’s power to edify:

“Thus a lively and lasting sense of filial duty is more effectually impressed on the mind of a son or daughter by reading King Lear, than by all the dry volumes of ethics, and divinity that ever were written.” — Thomas Jefferson, Letters to Robert Skip

His interests were as wide as they were strong, and his reading habits show this. No discipline was off limits to his curiosity, and he even crossed into architecture, geography, mathematics, and the natural sciences.

His Attitude Towards the News

Though newspapers were important to him as a politician, he shied away from reading them later in life:

“Indeed my scepticism as to every thing I see in a newspaper makes me indifferent whether I ever see one.”

I can relate to this feeling.

Although I still try to stay updated on current events, I find myself less inclined to read the news lately. I worry that what I’m reading might be politically biased or assembled in a hurry, and thus less intellectually nutritious than a good book.

In studying Jefferson’s reading life, I always find myself reminded about the power of old books to enlighten and inspire, as well as the importance of studying across disciplines to form a broad base of knowledge.

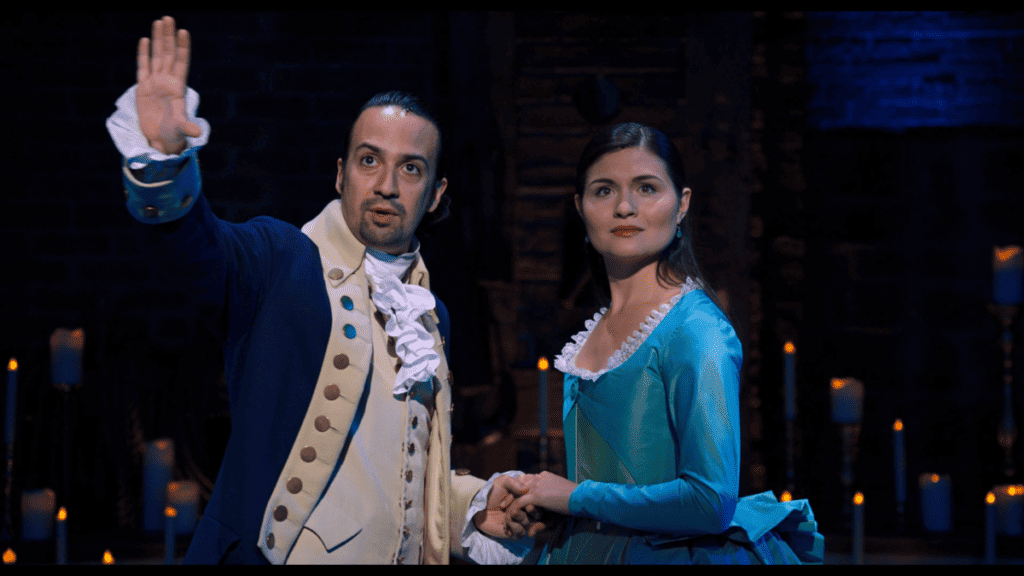

Alexander Hamilton: The Studious Autodidact

I still regularly play the soundtrack of the musical Alexander Hamilton when I’m in need of some inspiration.

A shower spent listening to “Non-Stop”, “Wait for It”, and “Alexander Hamilton” never fails to recharge my battery for study.

I’m sure that’s because I’m imagining what Hamilton would do if he were in my position: read.

Hamilton’s Intense Study Habits

Just look at how Ron Chernow, the Author of the biography that inspired the musical, describes his study habits while at college:

“He often worked past midnight, curled up in his blanket, then awoke at darn and paced the nearby burial ground, mumbling to himself as he memorized his lessons… A copious notetaker, he left behind, in a minute hand, an exercise book in which he jotted down passages from the Iliad in Greek, took extensive notes on geography and history, and compiled detailed chapter synopses from the books of Genesis and Revelation.” — Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton

One might assume that this intensity was present only because as an autodidact he felt behind and was working hard to catch up with his fellow college students.

But it was moreso a habit of mind that pervaded his entire life, before and after his few years of formal education.

From a young age, Hamilton was consumed by literary, and then political, ambition, and he knew that education was the best way to rise.

“Like Ben Franklin, Hamilton was mostly self-taught and probably snatched every spare moment to read.” — Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton

Forbes writer Joel Landau put it well when he wrote:

“Like so many Americans, Hamilton was an immigrant. And like many entrepreneurs, his education was anything but formal. He was tutored in the Virgin Islands and supplemented his education by reading books. He also dropped out of King’s College to fight in the American Revolutionary War alongside George Washington. Hamilton eventually completed his studies on his own to work as a lawyer before becoming the United States’ secretary of the treasury, a testament to his unwavering autodidactism.” — Joel Landau, Forbes

Whether it was law, government, poetry, or political economics, he was obsessive in his studies, and credits this attitude for much of his success.

“Men give me credit for some genius. All the genius I have lies in this; when I have a subject in hand, I study it profoundly. Day and night it is before me.”

Such passion drove him to incredible feats, including establishing the American financial system and penning the majority of essays in The Federalist Papers.

Alexander Hamilton’s life, the good parts of it at least, are a testament to the power of autodidactism.

Do you have what it takes to be an autodidact? Check out the six traits all successful self-learners have in common.

How Will You Make a Difference?

While it’s romantic to think of learning to be an end in itself, self-education becomes much easier to stick with and enjoyable to do if you’re doing it for a higher purpose.

The student of philosophy who uses that philosophy to live a better life or to teach others how to live a better life will spend far more time studying than the one doing it simply for pleasure or cultural capital.

The student of botany will find much more motivation to crack open that textbook if they’re planting a garden.

And the aspiring politician (we can only hope) will want desperately to know the history of their country in order to improve upon its weaknesses and amplify its strengths.

If I had to choose one big thing to take away from the self-education of these great men, it’s this: find strong personal reasons for your studies, and then attack them with deliberateness and intensity. Do this and learning, knowledge, and fulfillment will follow.

That said, consider joining my autodidact newsletter where I’ll help you study new topics on your own. If you sign up, you’ll get a free 8-step checklist for teaching yourself any subject, so you aren’t lost in the process: